The human side of the pandemic

As the world is trying to come to terms with the new coronavirus, Team MAPPOLA is doing its utmost to keep safe, working from home as best we can.

As an international team of researchers, recruited from across Europe, with family, relatives, colleagues, and friends in countries that are particularly badly affected by this crisis, we feel the full impact and force of this worldwide disruption.

We are fortunate in that we are able to continue our work – and even to be able to carry out research that, in fact, has some relevance in these difficult times. For pandemics are not, of course, a new phenomenon.

Anyone who has studied the ancient world will know of the plague that hit Athens, described in Thucydides and eternalised in the revolting, deeply troubling, and yet hauntingly beautiful final lines of Lucretius‘ poem De rerum natura.

But there is a lot more ancient poetry out there that records the impact of ancient epidemic diseases. (Fear not, we won’t go into retrospective diagnostics – we have no such skills: we will refer to epidemics where the ancient authors talk in terms of pestilentia or lues and the like, without any desire to carry out a body count, or an antibody count, to verify such claims.)

There are many texts that one might adduce, to illustrate the devastating impact of such diseases on human societies and communities in the ancient world, and we will discuss them in a forthcoming article (see below).

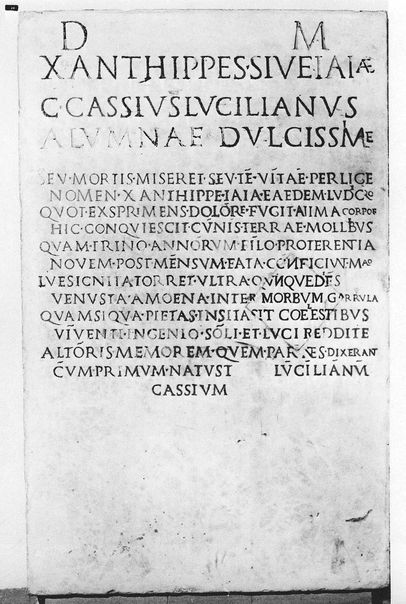

Here, we would like to show one particularly troubling case – commemorating the death of a young girl called Xanthippe, a.k.a. Iaia, whose cries of pain are preserved in an inscription from Parma, Italy, that seems to date to the third century A. D.

CIL XI 1118 (cf. p. 1251) = CLE 98 = EDR 082072. – Image source here.

D(is) M(anibus)

Xanthippes siue Iaiae.

C(aius) Cassius Lucilianus

alumnae dulcissim(a)e.

Seu mortis miseret seu te uitae perlige

nomen Xanthippe Iaia eaedem ludicro.

quot exsprimens dolore fugit anima corpore

hic conquiescit cunis terrae mollibus

quam trino annorum filo proterentia

nouem post mens(i)um ⌜f⌝ata conficiunt malo –

lues ignita torret ultra quot dies –,

uenusta amoena intellegens et garrula.

quam siqua pietas insitast caelestibus

uiuenti ingenio soli et luci reddite

altoris memorem quem parentes dixerant,

cum primum natust (!), Lucilianum Cassium.

To the Spirits of the Departed of Xanthippe a.k.a. Iaia.

Gaius Cassius Lucilianus (sc. had this made) for his sweetest foster child.

Whether you pity her death or her life, read to the end: her name was Xanthippe, or, in jest, Iaia. As the breath of life escaped her body, pushing out in pain, she rests here in the soft cradles of earth – she, whom the Fates, as they spin the years’ triple thread, diminished in an evil deed. An epidemic, ablaze, parched her over many days – her, the lovable, pleasing, intelligent, babbling child.

If the heavenly gods possess any sense of duty at all: restore her to living spirit, to sun, and to light: her, who remembers her foster-father, whom the parents appointed upon her birth, Lucilianus Cassius.

The expressive language of this piece has lost nothing of its disturbing force.

The breath of life is described as violently pushing to escape the little girl’s body (exsprimens dolore fugit anima corpore). Her body is tormented, roasted alive (torret), by the disease, ablaze with full force (lues ignita), for longer than anyone could bear (ultra quot dies).

All this makes one doubt heavenly justice, heavenly compassion. In utter desperation, the powers above are asked to return life, to the little baby – to allow the girl to see the sun-light again: a little girl, who had just discovered this world, a delight, beautiful, wide awake, babbling along.

Both Xanthippe’s very life and her death are thus pitiable, and the torment and despair of those left behind are palpable.

From a distance, a pandemic may seem like a medical and economic problem. But the numbers we get to read every day, the count of newly infected cases and the ever increasing number of deaths: behind every single one of them there is a human being who suffers, and behind every human being who suffers there are many more who suffer with them.

Yes, we must think of solutions to the medical issues and the economic turmoil to follow.

But we must not forget about the human side of things, either. The psychological impact of pandemic diseases on individuals and communities is profound, and we must offer compassion and help to those in need just as much as we must do our utmost to address and cure the suffering of those who have fallen ill. We are all in this together, as humans, across time, space, creed, and social class.

Xanthippe’s memorial is a powerful reminder of that.

We discuss a broad range of Roman verse inscriptions related to ancient pandemics from across the empire in the following article:

- Kruschwitz, P. (2020) Eine kleine Poetik der Seuche: Epidemien im Spiegel römischer Versinschriften. Gymnasium: Zeitschrift für Kultur der Antike und Humanistische Bildung. pp. 137-157.